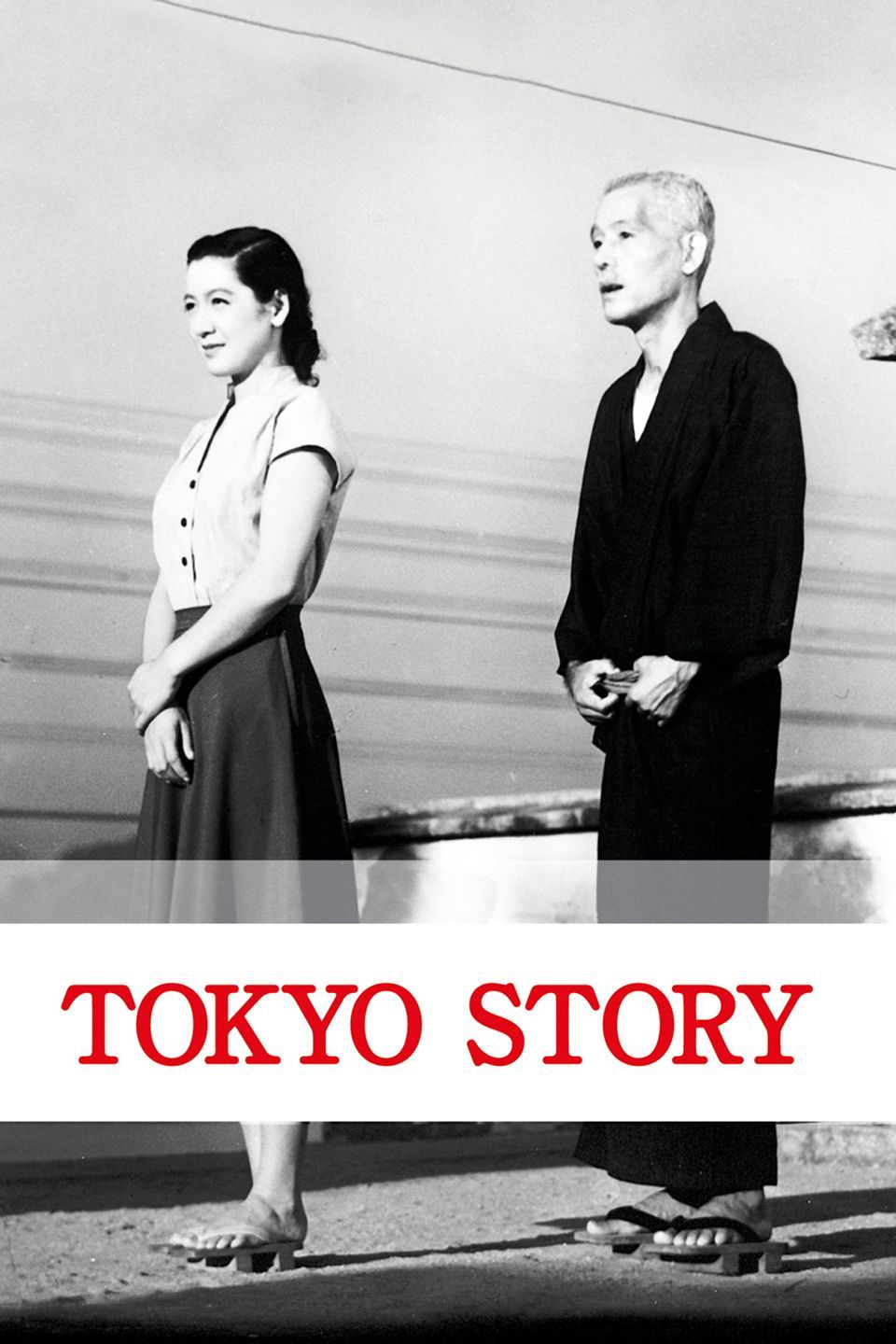

Tokyo Story

Directed by Yasujirō Ozu8.1100%93%

The elderly Shukishi and his wife, Tomi, take the long journey from their small seaside village to visit their adult children in Tokyo. Their elder son, Koichi, a doctor, and their daughter, Shige, a hairdresser, don't have much time to spend with their aged parents, and so it falls to Noriko, the widow of their younger son who was killed in the war, to keep her in-laws company.

Cast of Tokyo Story

Tokyo Story Ratings & Reviews

- cultfilmlikerMay 25, 2025Sayonara No notes. Simply beautiful. The stoicism is remarkable. Man I wish I at least visited Asia before I crippled my body and eyes Hilariously harsh wrt the fat shaming smh …..so I guess one note… WHAT ARE NOTES

- CrossCutCriticMay 7, 2025Tokyo Story The Familiar Ache of Aging and Absence “In this world, we walk on the roof of hell, gazing at flowers.” — Kobayashi Issa --- There are films that explain. Others that entertain. And then there are films that sit beside you and say nothing— because they know that nothing can be said. Yasujirō Ozu’s Tokyo Story is not about what happens. It is about what doesn’t. It is about a silence too sacred to fill, a kindness too late to matter, and the slow erosion of presence that we call modern life. The story is disarmingly simple: An elderly couple travels from their small coastal town to visit their grown children in Tokyo. They are greeted with politeness, inconvenience, and quiet dismissal. The children are not cruel—just busy. Preoccupied. Distant. As we all are. And that is Ozu’s genius: He never condemns. He simply observes. The camera remains low, unmoving, as if seated on a tatami mat, bearing silent witness to the ache of being no longer needed. We watch not a family breaking apart, but a family failing to notice it already has. The film unfolds like memory—slow, elliptical, gentle in tone but devastating in effect. Ozu doesn’t manipulate emotion. He trusts it. There are no close-ups of grief. No musical swells. Only quiet rooms, unfinished sentences, and a world moving forward without you. This is the cross Ozu reveals: Not the dramatic suffering of martyrdom, but the dull ache of being quietly forgotten by those you once held in your arms. The Unseen Cost of Ordinary Neglect The pain in Tokyo Story is not born of tragedy. No one is struck down. No great sin is committed. It is the pain of ordinary life—of well-meaning people slowly drifting away from each other out of habit, fatigue, or the quiet tyranny of modern ambition. The children are not villains. They are familiar. Koichi, the busy doctor, means well but cannot make time. Shige, the hairdresser, fusses with appearances but bristles with inconvenience. Even Kyōko, the youngest daughter, does not protest until it is too late. And so Shūkichi and Tomi, the parents, sit quietly in unfamiliar rooms, watching their children move around them as if they were already ghosts. They smile. They reassure. They do not complain. Their dignity is their sorrow. Only Noriko—widowed, childless, not even truly “family”—sees them. She offers her time, her presence, and most of all, her listening. She is not trying to fix anything. She simply stays. And in that act, the cross is revealed—not in grandeur, but in companionship. Noriko is the Christ figure in this story: Not victorious, not radiant, but faithful. She cannot take away their loss, but she refuses to let them carry it unseen. This is where Ozu’s theology unfolds—not with sermons, but in the devastating contrast between presence and absence. The children are too busy living to see what is dying. Only Noriko, in her sorrow, knows how to bear witness. And this is the cost we do not count: That love, unexpressed, becomes absence. That absence, repeated, becomes grief. That grief, ignored, becomes generational. The Grace of Staying Noriko stays. That is the miracle. She has no obligation. No reward. Her husband is dead. Her ties to the family are tenuous at best. But still, she stays—with them, beside them, for them. There is no fanfare in this. No luminous halo. Just a quiet faithfulness that holds the broken pieces without trying to glue them back together. This is grace in Ozu’s world: not intervention, but accompaniment. Not the power to change a story, but the mercy to share its weight. When Tomi nears death, it is Noriko who sits at her bedside. It is Noriko who holds her hand. It is Noriko who later weeps—not for what happened, but for what was missed. And this is where the film touches the cross. Not the bloody spectacle we’ve come to expect in Western iconography— but the hushed endurance of staying near someone else's sorrow, without needing to fix it. Ozu frames her in stillness—offering, receiving, waiting. She becomes the embodiment of Christ’s presence: gentle, unnoticed, fully there. There is a moment, small and unassuming, when Shūkichi thanks her for her kindness. She replies, “I’m not kind… I just got used to being alone.” And yet this admission only makes her mercy more profound. Because cruciform love is not born from strength. It emerges from lack. From widowhood. From ache. It is the mercy of one wounded person sitting with another and refusing to walk away. The Shape of What Is Lost After Tomi’s death, everything falls silent. Not dramatically. Not suddenly. Simply—quietly. The family returns for the funeral. They bow. They eat. They speak in clipped, awkward tones. And then they leave. Even here, Ozu resists sentimentality. There is no confrontation. No catharsis. Only the dull ache of routines resuming too soon, and the unbearable normalcy of loss. Shūkichi, newly widowed, wanders through his home like a man misplaced. No wailing. No lament. Just a stillness that feels eternal. And that is Ozu’s final gift: He does not show us how to mourn. He shows us what remains after mourning has faded. What remains is not memory—it is absence. A cup left unwashed. A fan left still. The scent of someone no longer there. We want redemption to feel like a sunrise. But in Tokyo Story, redemption arrives as quiet recognition: You were loved. You didn’t know it. Now it’s too late. And yet—even that is not the end. Because Noriko returns one last time. She offers her presence again, and Shūkichi, in his grief, gives her his late wife’s watch. Not as payment. Not as closure. As gratitude. It is a passing of time, of tenderness, of blessing. A small liturgy in the ruins. Here, grace does not fix. It follows. It bears witness to what was broken and does not look away. A Benediction in the Ordinary The film ends not with reunion, but with release. Kyōko, the youngest daughter, laments how selfish her siblings are. “They’re so inconsiderate.” And Shūkichi, with a faint, weary smile, replies: “Children look after their own lives… eventually.” There is no bitterness in his voice. Only acceptance. Not resignation, but relinquishment. This is Ozu’s final theology: That life does not resolve. It simply continues. That people do not become who we want them to be. They simply become. And yet— in this gentle letting go, a strange peace rises, like steam from a teacup. Because grace, in Ozu’s world, is not thunderous. It is domestic. Slight. Delicate as folding laundry or sharing rice. It is Noriko’s bowed head. Shūkichi’s hollow gaze. A train pulling away into the morning haze. And if we listen closely enough, we hear what the film never says aloud: That love is not proved by grand gestures, but by the act of staying near the unloved and naming them worthy. That grief is not a detour, but a door. That presence is the last form of prayer. Tokyo Story does not end. It abides. Like a blessing murmured in a house now empty. Like the ache that lingers long after someone is gone. Like a hand, once held, now resting alone— still warm with memory, still full of grace.